Sighting one of the nimble and graceful bighorn sheep performing a gravity-defying ballet on a rocky cliff is one of the chief delights for visitors to Yellowstone. About 300 bighorn live within the park, with most inhabiting the northern range. Mt. Washburn and the Gardner Canyon (between Mammoth and the North Entrance) are good areas for frequent viewings of the bighorn sheep.

While leaping from ridge to ridge, the bighorn sheep—especially the rams—carry a heavy load. An adult ram’s horns can weigh up to forty pounds and account for 8-12 percent of its body weight. Horns also denote social status in males, with the general rule being the bigger the horn the higher the ranking.

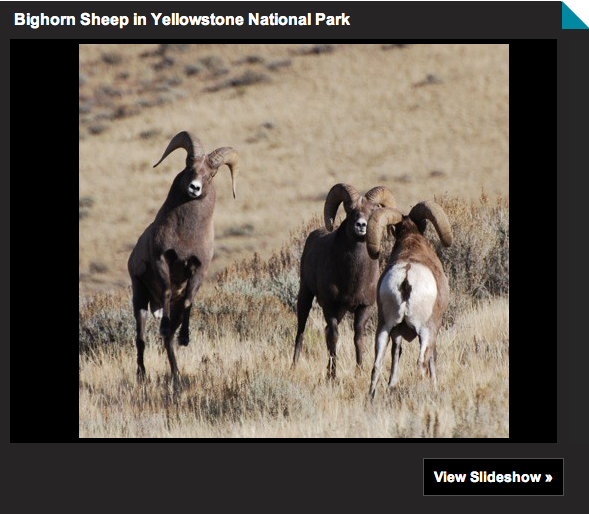

In November the bighorn sheep rut begins and as far as clashes go, the bighorn are pretty civilized. The rams “huddle” in a group showing off their horns and sizing each other up. If a subordinate does not concede, a dominant ram may assume the “low stretch” stance that indicates power. Then suddenly, the two rams may surge toward each other and clash in a dramatic crashing of heads and horns. Yet the incident ends very quickly and the rams may resume grazing or resting next to each other immediately after the fight

Last year I was lucky enough to observe a large bighorn herd during the rut. My favorite stance was the lip curl, a bighorn “funny face” made after a ram smells an ewe in order to determine her reproductive status. After the rams had fought for some time, the females moved near the huddle as if to say, “enough silly fighting!” Many of the eager males followed the ewes, strolling behind with their lips curled and heads lifted proudly in the air.

For all their abundance in Yellowstone, bighorn sheep in our country face many threats. Theodore Roosevelt is generally credited with bringing the sheep back from the brink of extinction in the early 1900s. Habitat erosion and climate change pose challenges for the bighorn. Exposure to livestock and even humans also put bighorns at the risk of contagious disease. A pink-eye epidemic in Yellowstone in 1982 decreased the park’s bighorn sheep population by almost 60%, but the animals have been slowly recovering at a rate of 7% growth since 1998.