Despite my making it a priority to carve out some hiking time once a week, I had not really taken an actual multiday, totally unplugged vacation since about 2007. So when the great folks at the High Sierra Camp Reservations called to let me know they had a last minute cancellation for three nights at Vogelsang, I didn’t even hesitate.

Despite my making it a priority to carve out some hiking time once a week, I had not really taken an actual multiday, totally unplugged vacation since about 2007. So when the great folks at the High Sierra Camp Reservations called to let me know they had a last minute cancellation for three nights at Vogelsang, I didn’t even hesitate.

For those unfamiliar with the rapturous, granite peak and alpine lake studded landscape that is Vogelsang, the Yosemite High Sierra Camp sits at 10,130 feet surrounded by the mountains of the Cathedral Range. Access is by hiking or horseback riding only, but the quaint camp provides tent cabins and meals, thus eliminating much weight from your pack. The seven-mile hike from Tuolumne Meadows saunters through lupine filled meadows and affords splendid views of Mt Conness, North Peak, Fletcher Peak, and Rafferty Peak. Once you arrive at camp, Fletcher Peak lords over the alpine meadow and in the evenings the sunset and alpen glow paints Fletcher and the other granite peaks in purple and pink hues.

Above Vogelsang Lake

Above Vogelsang Lake

Vogelsang also affords day hiking access to some jaw-dropping scenery in the Cathedral Range, and if you are willing (and able) to venture off trail, you can spend a whole day hiking without seeing another person.

What to share? During my wonderful sojourn at Vogelsang, I snapped about a thousand photos and wrote about twenty pages on my experience. I had a tough time narrowing down the highlights, but here’s my attempt.

Gallison Lake: “O!, the Joy,” exclaimed Capitan Clark at the wonders he saw during his famous trek across America. I am stealing this phrase to describe my day wandering in the Gallison Lake basin by following Lewis Creek to its outlet just below Simmons Peak. This area just vibrated with Sierra Nevada splendor.

Gallison Lake (photo by Beth Pratt)

Gallison Lake (photo by Beth Pratt)

Ranger Dave: A dedicated and passionate bunch of park rangers lead people on High Sierra Loop trips and Ranger Dave is no exception. I had not seen Ranger Dave in years, and it was great to reconnect, especially since he did his evening program on frogs! His knowledge of Yosemite is incredible and his enthusiasm for the park contagious.

With Ranger Dave or Danger Rave

With Ranger Dave or Danger Rave

Pika Whispering: This trip just confirms that I am a pika magnet (see my Picnic with a Pika entry for more evidence). On a slope of an unnamed lake above Townsley Lake, I sat mourning my lost photo of a toad (see below) when suddenly I head a familiar chirp, chirp. Not ten feet away a pika posed on a rock, saying, forget the silly toad, and take my photo. Two of them played for about 30 minutes in front of me.

Pika posing for the camera (photo by Beth Pratt)

Pika posing for the camera (photo by Beth Pratt)

Pika munching on lupine (photo by Beth Pratt)

Pika munching on lupine (photo by Beth Pratt)

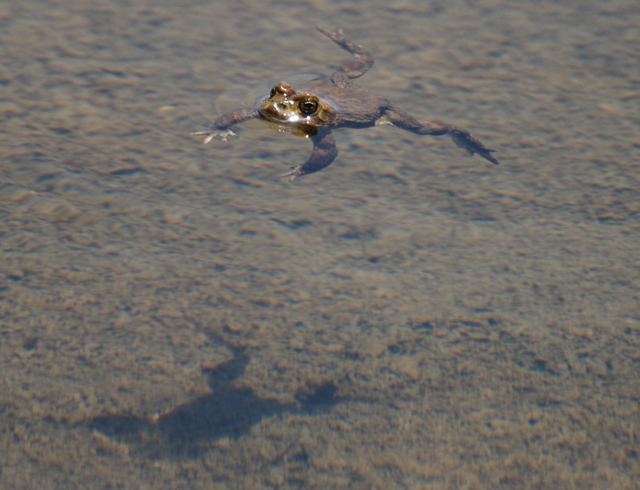

The Toad That Got Away: I missed the amphibian photo op of the year, but was consoled by a pika (see above). On a ridge at about 10,400 above an unnamed lake, what I think was a Yosemite toad lumbered by me, but made it into a small den before I could take a photo. Very cool sighting. I saw no more amphibians, but did find many tadpoles during my wanderings.

Tadpole (Pacific chorus frog?) near Vogelsang (photo by Beth Pratt)

Tadpole (Pacific chorus frog?) near Vogelsang (photo by Beth Pratt)

Why I Love Convection: Convection was the word of the day for my hike into Vogelsang—the air was up to some mischief, but the rambunctious winds cooled off what would have otherwise been a hot seven-mile hike. As weather patterns go, the two full days in July of cumulus congestus swirling around the basin is an odd one for the Sierra—usually it’s blue skies and we lack the daily build up of the Rockies. For my hike out, the sky birthed some great cirrus and cirrus cumulus clouds.

Cirrus clouds over Unicorn and Cathedral Peaks (photo by Beth Pratt)

Cirrus clouds over Unicorn and Cathedral Peaks (photo by Beth Pratt)

Storm clouds over Fletcher Peak (photo by Beth Pratt)

Storm clouds over Fletcher Peak (photo by Beth Pratt)

Sunsets: Viewing the sunset on a ridge below Gaylor Lake was a nightly ritual. That’s Cloud’s Rest to the right and the back of Half Dome peaking out next to it.

Sunset over Half Dome and Clouds Rest (photo by Beth Pratt)

Sunset over Half Dome and Clouds Rest (photo by Beth Pratt)

Sunset colors at Vogelsang HSC (photo by Beth Pratt)

Sunset colors at Vogelsang HSC (photo by Beth Pratt)

Thanksgiving in July, or Why You Are Never Hungry at Vogelsang: The crew at Vogelsang is fantastic and boy can they cook. A Thanksgiving feast the first night (with a pretty splendid veggie option, thank you), pesto ravioli, raspberry pancakes, mint chocolate cake –you get the idea. Cooking at 10,000 feet and on propane isn’t easy, so kudos to the great crew—Chris, Matt, Dan, MaryBeth, Shad, et al. And thanks for the great route tips as well.

Hanging Basket Lake: Nestled in a small cirque below Fletcher Peak and above Townsley Lake, Hanging Basket Lake is worth the scramble up talus to view this sublime body of water.

Hanging Basket Lake (photo by Beth Pratt)

Hanging Basket Lake (photo by Beth Pratt)

The aqua green waters of Hanging Basket Lake (photo by Beth Pratt)

The aqua green waters of Hanging Basket Lake (photo by Beth Pratt)

Sierra Nevada, as in hotbed of chipmunk diversity: As my friend John Muir Laws taught me, the Sierra “is a hotbed of chipmunk diversity.” Not sure what subspecies these two critters were, but they are still cute.

Playful chipmunks (photo by Beth Pratt)

Playful chipmunks (photo by Beth Pratt)

Wildflowers Gone Wild: Vogelsang did not disappoint and earned again it’s reputation for wildflower splendor during my trip, yet some species had emerged earlier than usual given the dry year and the lupine definitely was diminished.

Paintbrush in front of Fletcher Lake and Vogelsang Peak (photo by Beth Pratt)

Paintbrush in front of Fletcher Lake and Vogelsang Peak (photo by Beth Pratt) Monkeyflower (?) below Hanging Basket Lake (photo by Beth Pratt)

Monkeyflower (?) below Hanging Basket Lake (photo by Beth Pratt)

Packers, saviors of my back: I met another Yosemite friend I had not seen in years, the wonderful packer Sheridan, and we reminisced about old times. She also gave me the perfect end to my vacation when she discovered she had room on her mule train for my pack. Instead of carrying the heavy weight out, I instead spent the hike searching for frogs and tadpoles.

Sheridan, the fabulous packer/guide (photo by Beth Pratt)

Sheridan, the fabulous packer/guide (photo by Beth Pratt)

Campmates, i.e., fellow Yosemite enthusiasts: Although I love solitary hiking by day, the evenings at Vogelsang are full of enjoyable encounters with fellow Yosemite lovers and some pretty cool people: a group of friends honoring the late Ann Otter of the Yosemite Conservancy with their annual trek to Vogelsang (some had been coming for 30 years); the reigning woman’s champion in the 75-79 age group for the Boston Marathon—at 78 she had run the race 8 times and we were all in awe of her; a man with fifty years of memories of Yosemite, including the firefall; a family from southern CA with three motivated young adults; a couple with a nine year-old boy who was doing his first hike—the entire loop trip!; a couple from Petaluma who I had soem good discussions about resource management; a developer of laser technologies who had run the Mt Diablo 50K, an environmental writer for Bloomberg, a couple with a son who is a nuclear physicist from MIT (we had some interesting energy discussions), and many others. Meal times at Vogelsang are never dull!

Coda: A brief journal entry I wrote during my trip:

“For me the sun on my face will always be a blessing, the sound of running water a comforting hymn, the voice of the wind a benediction, and the blue sky an aspiration.”

I belong among the wildflowers

I belong among the wildflowers