Doug Smith, Yellowstone Wolf Project Leader, with wolf 472F (photo by NPS Wolf Project)Biologist Douglas Smith has led the Yellowstone Wolf Project since its inception and has studied wolves for almost thirty years. He co-authored with Gary Ferguson the book Decade of the Wolf, which details the historic wolf reintroduction effort in Yellowstone. I spoke with Douglas on January 20, 2010.

Doug Smith, Yellowstone Wolf Project Leader, with wolf 472F (photo by NPS Wolf Project)Biologist Douglas Smith has led the Yellowstone Wolf Project since its inception and has studied wolves for almost thirty years. He co-authored with Gary Ferguson the book Decade of the Wolf, which details the historic wolf reintroduction effort in Yellowstone. I spoke with Douglas on January 20, 2010.

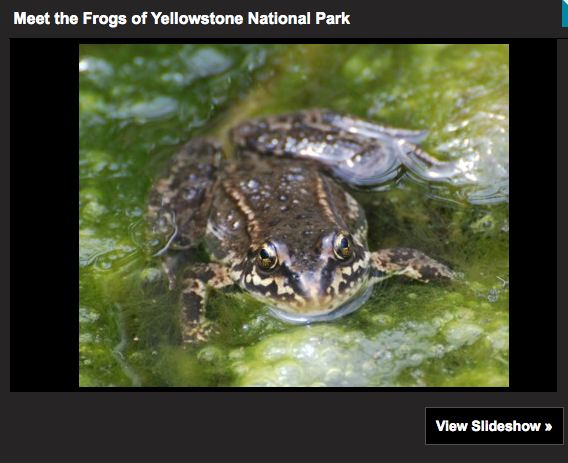

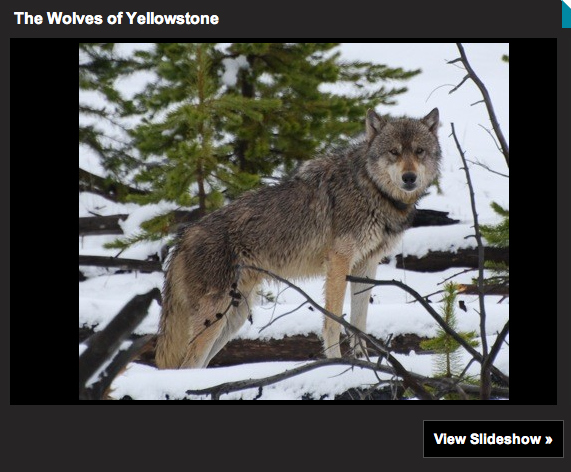

Click here to view a photo slideshow of Yellowstone's wolves.

You’re in the middle of conducting your winter research on the wolves in Yellowstone. What are you finding for 2009 results?

We experienced a population decrease, which is the first time we’ve had two consecutive years of a decline. Since the reintroduction in 1995, the population decreased only four times: in 1999, 2005, 2008, and 2009. This year we counted between 96-98 wolves—the population has not dipped below 100 since 1999. We had to hyphenate the count for the first time because we’ve lost radio tracking with two packs, Delta and Belcher, on the southeast and southwest areas of the park.

Where have the decreases in population taken place?

For research purposes, we’ve started to divide up the wolves into two segments: the northern range and the interior. Our team counted 40 wolves in the northern range as compared to 56 in 2008—this is where we’ve experienced most of our population loss. The interior packs are largely stable—they decreased this year to 56-58 from the mid-60s in 2008. Overall, however, the numbers represent that we’ve lost almost half of our wolves in two years.

What do you think is the reason for the decline?

What is new and significant is that for the first time in our study, we think the decline isn’t associated with disease, but with food stress. During our field time, we found a wolf that had starved to death—this happens pretty rarely. We also observed multiple signs of malnutrition.

We’re not alarmed about the losses or the cause because we’re beginning to think that the wolf population is developing a stable equilibrium with the available food in the park. In 1995 when they were reintroduced, this was the best place in the world to have wolves due to the abundance of food. Using the peak wolf population of 174 in 2003 as a baseline isn’t a good measure because it doesn’t reflect that the wolves probably had an inflated food source. Now we think they are finally coming into balance with the food supply for Yellowstone.

The elk population in Yellowstone has also experienced a decline, which most people attribute to the wolf reintroduction. Is this accurate?

The park has lost half of its elk population—but it’s not all attributable to wolves. What I like to stress is that having fewer elk is not a bad thing. We had one of the densest elk populations in the world. By bringing that population back into the proper balance, we’ve allowed other life forms in the park to flourish.

Should the wolves be protected under the Endangered Species Act?

The wolves have biologically recovered and should be delisted. But they have not politically recovered and people can’t agree on how to manage them. You can’t talk about wolves without talking about anti-wolf sentiment. It appears that when you can hunt wolves, you reduce the level of animosity toward them. In the end wolves are better served from taking them off the endangered species list. It’s a form of conflict management and a benefit to wolf conservation overall.

What pack stood out this year in your research?

Mollie’s pack has become very successful at killing bison—no easy task even for a wolf. 495M, the largest wolf ever recorded in Yellowstone at 143 pounds, leads the pack. Usually the packs will start hunting bison in mid-to-late winter, but Mollie’s started right out of the gate. Mollie’s pack also appears to have bounced back from a mange outbreak—a great new development since most wolves usually don’t recover.

You lost one of your most famous wolves this year—302.

The story of the year was probably 302, the most popular wolf in Yellowstone. The Quadrant pack probably killed him in a territory dispute. We know his story well since we’ve been following him for years. Most wolves live to about 4 ½ to 5 years on average—he was probably nine. We had nicknamed 302 “Mr. Casanova.” Most wolves assume a pretty monogamous breeding position in their pack structure and have no interest in philandering. But 302 had a wandering eye. He would leave his pack during breeding season to court females in other packs. It’s ironic that 302 had a huge following—people loved him—but he was probably the most unethical wolf we had because of his extensive “affairs.”

There have been reports that the wolves are harder to spot in Lamar Valley these days. Is that true?

Lamar provided a hub for the Druids, who are now in bad shape: only two wolves in the pack are without mange, they lost their alpha female, and their alpha male is on the way out. Some good places to see wolves are at the west end of Lamar by Slough Creek or Little America—the Lava pack of three wolves seems to be hanging out there. The Agate pack travels around Specimen Ridge, and the Quadrant pack has been sighted near Swan Lake Flats and in Mammoth Hot Springs. Today you could hear the pack howling right in our offices in Mammoth.

What will be the focus for the Yellowstone Wolf Project in 2010?

Our research continues to be a source worldwide for the study of predator/prey relationships, and also one of the best resources about a wolf population unexploited by human behavior. Genetics is another key area of focus. We’re doing some groundbreaking work in looking at the genetics of wolf societies and its relationship to their behavior.

What I find so unique and important about the wolf project is its longevity. I recently read that 80% of wildlife research has a duration of three years or less. We’re in our 16th year. We tend to get caught up in the complexities of the web of life, but sometimes the simple things provide so much information. For us, being here in the park and watching the wolves day after day has been invaluable to our work.

For more information on the Yellowstone Wolf Project visit the websites of the National Park Service and Greater Yellowstone Science Learning Center.

The Yellowstone Wolf Project needs your support. Consider making a donation to the Yellowstone Park Foundation today to help fund their important work.

To observe wolves in Yellowstone, take a field class with the non-profit Yellowstone Association or book a wildlife watching vacation package with Yellowstone National Park Lodges.

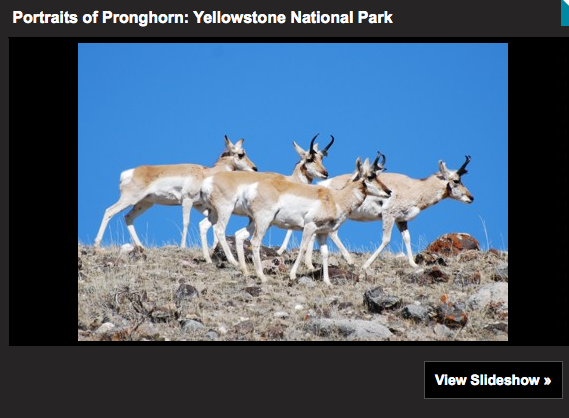

NPCA's Joe Josephson leads a group on a hike following the migration of Yellowstone's pronghorn. Photo: Beth PrattAlthough the focus of yesterday's outing was supposed to be pronghorn, the musical bugling of the rutting elk resounded throughout, and the group encountered several herds, and a few dueling bulls. Yet even with their less showy courtship ritual (primarily a male pronghorn continually herding his harem), the pronghorn did not disappoint. Participants following the footsteps of the ancient animal encountered a small group on the shoulder of Mt. Everts in Yellowstone National Park and watched in delight as the animals loped across the hillsides.

NPCA's Joe Josephson leads a group on a hike following the migration of Yellowstone's pronghorn. Photo: Beth PrattAlthough the focus of yesterday's outing was supposed to be pronghorn, the musical bugling of the rutting elk resounded throughout, and the group encountered several herds, and a few dueling bulls. Yet even with their less showy courtship ritual (primarily a male pronghorn continually herding his harem), the pronghorn did not disappoint. Participants following the footsteps of the ancient animal encountered a small group on the shoulder of Mt. Everts in Yellowstone National Park and watched in delight as the animals loped across the hillsides.